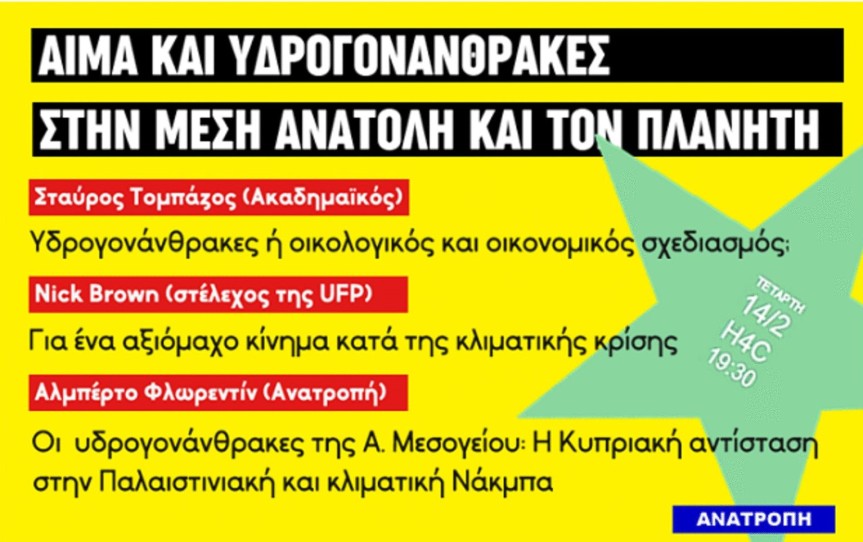

Here follows Nick Brown‘s presentation in the discussion organised by ANATROPI on Feb 14, 2024 in Nicosia, under the general title Hydrocarbons and Blood in the Middle East and the Planet. Nick Brown is a student and a founding member of United for Palestine in Cyprus. He is a member of Socialist Alternative in Australia.

Για το κείμενο στα ελληνικά πατήστε το link εδώ

If we can remember back to the time just before the pandemic — in 2019 — the world saw an unprecedented advance in mass consciousness about the climate catastrophe and ecological crisis we are currently facing.

The climate crisis is no longer perceived, as it was earlier as a concerning event on the horizon but a current reality that we are now all living in.

This sense was expressed with the emergence of a significant global youth movement mobilising at its peak 4 million people globally on the 20th September 2019, including 1.4 million people in Germany.

Subsequent weeks saw many million strong global mobilisations.

It was not only students but teachers and other workers who came out at a certain point taking work off for the protest.

The movement expressed the anger that many young people and millennial parents have been feeling — that their future is being robbed for the sake of profit and plunder of the Earth’s resources.

It also fed into what is a growing sense that our society is in a state of permanent crisis: climate change, pandemics, growing war and imperialist intervention and the extreme cost of living – all intersect to destroy any sense of certainty about our future.

Greta Thunberg, the most well known leader of this movement, represents much of the thinking that has gotten so many young people into the streets. Her consistent criticism at global forums and impressively principled take even on the issue of Palestine has been an inspiration for millions.

As Greta has pointed out, while we fight for a just world to live in, the rich and powerful have their global conferences for what? To talk about targets they know they will never achieve and to moderate the science as much as possible to sow the illusion that the climate crisis is still off in the distance and not an immediate emergency.

The UN Climate Change Conference (COP) is the primary example of this deplorable state of affairs. Tasked as the institution to guide the world economy to stay below 1.5C warming it has not only failed to achieve this task (set by itself), but is actively facilitating a cover up of the capitalist system which continues to extract fossil fuels and pollute.

COP28 last year was a joke. The president of this festival of lies was Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber — CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC). Who a week before the conference claimed that there was no science backing up the need to abandon fossil fuels to keep within the 1.5C warming target.

It is frankly satire that this man whose company ADNOC announced 150 billion dollars of investments for new fossil fuel projects in 2022 was allowed to be humanities leading representative for dealing with climate change. Even worse still — the event is now being used by fossil fuel capitalists to network and create new deals for further extraction according to leaks published by the Guardian and the Centre for Climate Reporting.

There is a huge rift in our society — on the one hand the massive scale of the current ecological crisis. As has been seen in the last summer where the Canadian northern forests were almost constantly on fire, huge heatwaves across Europe and a few years ago the Australian Black Summer fires, among countless other disasters.

And on the other hand — the complete impotence of attempts to create a greener capitalism, the expansion of extracting fossil fuels globally and the total disinterest of the political class to implement radical change — This obvious rift has lead to a sense of desperation particularly amongst the youth.

The climate strikes were not driven by specific hopefulness and positive program, but by a desperate attempt to disrupt the status quo with the aim of putting the breaks on continued fossil fuel extraction.

The pandemic, unfortunately, slowed much of these mobilisations and has allowed many governments in the west to move from a state of defensiveness to one of getting control of the narrative again.

Biden’s so-called Green New Deal and many other proposals — particularly the emphasis on EVs and individual sustainable energy solutions — seem to offer an alternative to many shocked that nothing has been done.

However, we have to be clear, promoting individual green consumer choices is a cover for the reality of industrial scale emissions. Regardless if every individual drives an EV, the scale of extraction of natural gas in particular for the global economy is still setting us on a course for disaster.

There is a further issue for the movement. That is its internal politics. There have been many different strains of politics leading the resistance to the climate crisis over the last five or so years.

Extinction Rebellion is a notable example. However, within the school strike movement itself there have been multiple perspectives.

In Australia, much of the school strike leadership have quietened their criticisms now that we have a Labour government in power — despite them approving new coal mines and overseeing a historic expansion of the natural gas export industry.

The critical divide in perspective comes down to how we understand the function of these mass actions.

Are protests just a mechanism to pressure governments into action or are they a starting point for deeper and more disruptive forms of struggle?

The first perspective pushes for a more conservative approach.

Fundamentally, they see that the system itself is not the issue — but that there are just some greedy fossil fuel companies making the world a worse place. Parliament structurally as the highest elected power of the state has the ability, therefore, to crack down on these companies.

Protesting, then, just becomes another appendage of a lobbying strategy to the government.

However, if the last almost 30 years since the Kyoto protocol has shown us anything, it is that despite the best efforts of environmental lobbyists and scientists producing huge volumes of evidence the fossil fuel economy and its parliamentary representatives will not falter in the face of the “truth”.

In this light the mass activity of students and workers during the climate strike and other ecological justice actions has to be the starting point for a challenge to the whole system.

The fossil fuel industry is built into the capitalist system — as a mechanism of profiteering, a mechanism of control through imperialist competition and the powering of the world’s war machines.

The irrational economic structure of capitalism does not allow within itself the rapid break that is required to move to a totally decarbonised economy.

For the movement, that is why we must grow a new generation of young anti-capitalist activists to argue for a different way forward and not limit play by the rules of parliamentary games of the major parties. It also means infusing working class activity into the movement.

Students have a tremendous power to disrupt and force political issues in public life. However, they lack the economic power that workers have when organised.

A great example of what workers can achieve both in-terms of their own living standards, but, also for greater ecological demands comes from a huge struggle waged by workers in New South Wales, Australia in the 1970s.

Amongst a broad radicalisation of the society, including the anti-Vietnam war movement and the black power movement, workers from the Builders Labourers Federation (construction workers) lead a massive campaign known as the ‘Green Bans’.

The face of Sydney today would look totally different if it was not for their actions. Through a targeted strike movement they successfully stopped the destruction of most of the green spaces in Sydney dist. for urban development. For example, the botanical gardens (which would have become a parking lot), Kelly’s bush an important natural reserve and also low density working class public housing.

This meant defying more conservative forces even within the trade union leadership, barricading sites planned for development and engaging with the broader social movements outside of the union.

Today, workers having a say over the economy and their work places will be essential to both stop the destruction of green sites, but more importantly today, the halting of new oil and gas projects and importantly to demand a just transition for those workers that are in the industry.

An inspiring example is dockworkers in Ireland. In 2019 after finding out that their workplace was being shut down due to bankruptcy: they occupied the site and demanded the government nationalise and repurpose the sight for sustainable energy production. And that training be provided on top of existing skills for them to continue to make a living. These examples offer a small glimpse of the direction our movement needs to take if it intends on challenging the power of fossil capital.

While the movement for climate justice in 2024 is certainly at an ebb point, there will most certainly be further struggles in the near future — most likely stimulated by extreme weather events.

In fact, despite the ebb of the climate strikes, there have been some important direct action struggles continuing. In Australia, there have been multiple small scale lock-ons over a series of new coal projects in Queensland which have cost corporations tens of thousands. In November last year an action of around 3000 stopped the shipment of coal for 30 hours. This was an important action as it targeted the most important site of emissions in Australia — it’s export industry. Both sides of government have argued that we should not worry because Australia is not such a big polluter compared to other countries with larger populations. However, if you include fossil fuel exports into the country’s emissions they skyrocket. The slogan ‘don’t dig it — keep all fossil fuels in the ground’ has been an important one against a government that doesn’t want to take responsibility for the climate crisis.

The broader atmosphere of crisis and particularly with so many people mobilising for Palestine recently can give people the experiences which drive new movements in other fields.

One example, is to connect Israel’s military dominance in the region with the West’s ability to exploit the natural gas resources here.

If we look back at our previous example of the Builders Labourers Federation — its dynamic actions on the environment and other social issues could have only happened in the context of a broad politicisation of the society due to the Vietnam war. Could the Palestine movement have this effect here? It is difficult to say for certain.

Ultimately, wherever we find ourselves we need to be pushing on toward the next step in the struggle for the movement to smash fossil capitalism. Whether it means getting the first protest in our city to happen, or organising our classmates to walk out on strike or building workers organisation capable of disrupting the fossil fuel industry. The fight as the kids have said again and again is a fight for our future – for humanity’s future.